I. Introduction: A Tale of Two Sports Worlds

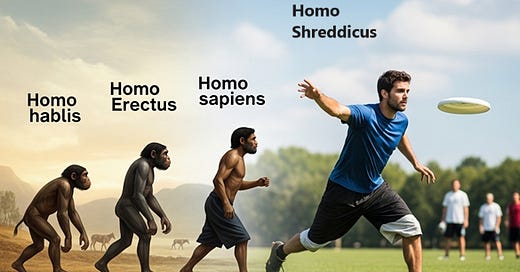

The stories of most great sports are, at their heart, stories of evolution. Baseball, football, and basketball all began in rudimentary, often clumsy forms. They made mistakes. They revised. They improved. The end result is a series of enduring institutions—refined over time, tested through competition, and sharpened by necessity.

Here are three case studies on the massive amount of revision that Basketball, Football and Baseball all went through within their first 50 years or so.

Interestingly, 110 years ago, dribbling was almost outlawed because it destroyed the game. Now history is repeating itself.

As of now, Ultimate Frisbee hasn’t has a single major revision in the past 50 years.

Ultimate Frisbee, a sport born from countercultural optimism, has spent more than five decades resisting transformation. A sport whose refusal to evolve has not only stalled its growth, but made it a masterclass in how ideology can arrest innovation.

While basketball once debated banning dribbling and the jump shot—and wisely did not—Ultimate Frisbee actively clamped down on innovation. While football moved from chaos to structure and baseball tweaked its rules to preserve equilibrium, Ultimate doubled down on sacred tenets that had long ceased to function. This thesis explores how Ultimate Frisbee became an ideological cul-de-sac: a game so deeply tethered to its origins in the New Games Movement, so committed to a flawed deadball ruleset within a continuous action structure, that it remains locked in a perpetual adolescence, unable to mature.

II. The New Games Movement and the Ideological Foundations of Ultimate

Ultimate Frisbee was birthed during a time of great cultural flux. It was the 1960s, and a wave of idealism swept across American youth. The New Games Movement, an experiment in community-based, cooperative play, was its ideological parent. The game's first rules—written by three teenagers with little to no competitive sports experience—reflected this: emphasis on fun, inclusion, self-officiating, and a rejection of traditional sports aggression.

The founding document that governed Ultimate Frisbee from the 1980s forward (the 8th edition rules) did not merely lay out mechanics—it canonized a worldview. A pivotal phrase from these rules—"protection of these vital elements is essential for the game's survival"—transformed ideological commitment into orthodoxy. The vital elements were self-officiating, inclusion, and fairness. In theory, this sounded noble. In practice, it created an environment hostile to competitive integrity, growth, or meaningful revision.

III. Uglimate and the Growing Pains of a Game in Denial

By the 1980s and into the 1990s, Ultimate was no longer a backyard pastime. It had become a competitive battleground played primarily by testosterone-driven young men in college settings and within the UPA’s National Fall Series. Predictably, the honor system began to fail. Arguments and fights erupted. Fouls were weaponized. Line calls were disputed. Tournaments turned toxic. This was the Uglimate Era—a period of high drama and low sportsmanship that should have been recognized as a call for reform.

But instead of overhauling the game to match the intensity and structure of other competitive sports, the UPA doubled down. They didn't abandon ideology; they fortified it. Observers were introduced—not to replace self-officiating, but to preserve it. In the face of growing chaos, the governing body chose to protect the symbolic purity of Ultimate rather than its functional integrity.

IV. The Frank Huguenard Hypothesis: Genius Rejected

Within this rigid ideological structure, innovation was not seen as evolution—it was seen as heresy. Enter Frank Huguenard. In the 1980s, Huguenard introduced a comprehensive offensive system known as Shredding. It combined fluid movement (what he called dribbling), offensive leverage (Triple Threat Principle), and a dynamic understanding of spacing and timing. It was legal, strategic, and devastatingly effective.

But Huguenard didn’t look or sound like the sport’s elite. He wasn’t crowned by championships. He wasn’t part of the inner circle. Instead, he was dismissed, mocked, and ostracized. The governing bodies—composed largely of those who had benefitted from the sport’s upside-down structure—failed to see that Shredding was not a gimmick but a fundamental challenge to their paradigm. The rejection of Huguenard wasn’t about tactics. It was about epistemological threat. If Shredding worked, then everything they believed about the game was wrong. And that, they could not accept.

V. Sports That Grew Up: A Comparative Lens

Consider the growing pains of other sports. Basketball nearly outlawed the jump shot and dribbling. But it didn’t. It absorbed the disruption and became better for it. Football added downs, neutral zones, hash marks, referees, and safety equipment. Baseball eliminated soaking, legalized gloves, lowered the mound, and embraced statistical science. All three sports evolved because their cultures understood something Ultimate never has: no founding moment is sacred enough to be immune to revision.

Ultimate, by contrast, has treated its founders’ teenage vision as gospel. The governing structures are built around protecting the original sin of the game: the dead-ball-continuous-play mashup. Fouls don’t stop the game, but players can stop play at will. Momentum violations, traveling infractions, and pivot abuse go unpunished. And those who suggest reform are labeled enemies of Spirit.

VI. Ideology as Incarceration: How a Sport Was Frozen in Time

Ultimate’s stagnation is not a failure of athletes. The sport is filled with talent. It is not a failure of creativity—many players long for a more expressive version of the game. It is a failure of governance rooted in ideological rigidity. Self-officiating, Spirit of the Game, and egalitarianism are not tools—they are articles of faith.

And when faith governs sport, dissent becomes sin.

By treating growing pains as existential threats rather than evolutionary opportunities, Ultimate rejected its moment of transformation. The game didn’t need a band-aid (Observers); it needed a scalpel. Instead, innovation was punished. Exceptionalism was resented. And mediocrity—so long as it aligned with orthodoxy—was rewarded.

VII. Take Your Medicine: A Call to Collective Humility

There comes a time in every institution’s life cycle where it must take its medicine. Ultimate Frisbee is long past due. The governing bodies, elite players, pseudo-successful coaches, and insular influencers need to accept the obvious truth: the sport has stalled. It has been stagnant for decades. It garners little respect from the broader athletic world. New talent rarely enters. Teams barely practice with intention. Coaching is almost nonexistent. The competitive ecosystem is an illusion. Disc golf, a solo sport with no defense and minimal movement, is dwarfing it in growth, media presence, and cultural legitimacy.

This should be a crisis. Instead, it’s a shrug.

The burden should not rest on Frank Huguenard to prove that Shredding works. The burden should rest on the gatekeepers of the game to justify why Ultimate is worth saving in its current form. If they cannot provide that defense—if they cannot explain why innovation is silenced, why exceptionalism is punished, and why excellence is mocked—then they must face the medicine: admit the game is broken. Admit that the founders got it partially wrong. Admit that Ultimate must, for the first time in its history, undergo a true revision.

If basketball, football, and baseball had been governed with this level of ideological fragility, they would have died in their infancy. Ultimate must decide: will it double down on the comfort of a failing orthodoxy, or will it open its arms to the heretics who saw the future before it arrived?

VIII. Conclusion: A Sport at the Crossroads

Today, Ultimate remains obscure, misunderstood, and structurally broken. ESPN deals and pro leagues have not changed that. Because the core has never changed. The same game mechanics that broke down in the 1980s are still intact today. And the one player who most clearly exposed the flaw—Frank Huguenard—remains an outsider.

The legacy of Ultimate Frisbee will not be determined by how well it protects its ideals, but by whether it can revise them. The game’s salvation lies not in tradition, but in courage. If basketball, football, and baseball could evolve from their humble origins to global dominance, so too could Ultimate. But only if it learns the same lesson:

Genius doesn’t ask permission. It tests the boundaries until the boundaries move.

Frank Huguenard did exactly that. And if Ultimate ever wants to become what it was meant to be, it must stop punishing the people who remind it of what it could be.