I. Introduction: The Myth of Eternal Baseball

This article reflects on the evolution of baseball's rule structure and cultural framework, tracing its transformation from a disorganized bat-and-ball game in the 18th century to a codified and professionalized American pastime by the early 20th century.

Modern baseball is often romanticized as an unchanging tradition, a game preserved in amber since its so-called invention by Abner Doubleday in Cooperstown, New York. But this myth masks the complex and often chaotic evolution of the sport. In truth, baseball has undergone dozens of major rule changes and systemic revisions, each reshaping its competitive balance, spectator appeal, and cultural significance. These revisions—spanning from the 1840s to the early 1900s—were essential for transforming baseball from a rowdy, regional folk game into America’s most refined and cherished pastime.

⚾ Major Rule Revisions That Transformed Baseball

1845 – The Knickerbocker Rules

First formal rulebook (by Alexander Cartwright)

Introduced foul territory, tagging instead of soaking, 3 outs per side

Marked the end of “soaking” (throwing ball at runner to get an out)

1857 – Nine-Inning Standardization

Games standardized to 9 innings (previously played to 21 runs)

Established 9-player teams and set pitching distance

1864 – No More “Bound Outs”

One-bounce catches no longer counted as outs

Required clean fly-ball catches, increasing athleticism

1871 – Professional League Formed (NA)

First openly professional league; exposed problems of gambling and inconsistency

Paved the way for stronger centralized governance

1876 – National League Founded

League-controlled scheduling, contracts, and rules

Began treating baseball as a business and professional institution

1884 – Overhand Pitching Legalized

Changed pitcher-batter dynamics; made pitching strategic and dominant

1887–1893 – Strike Zone and Walks Formalized

Four balls = walk (down from 9 balls originally)

1893: Pitching distance moved to 60' 6", transforming the role of the pitcher

1901–1903 – Foul Balls Count as Strikes

Prevented batters from endlessly fouling off pitches to stall

1903 – First World Series

Cemented baseball as a national institution with a unified championship

1920 – End of the “Tired Ball Era”

Baseballs from 1900-1919 were considered to be deadball (soft, old and tired)

Introduction of livelier balls, banning of spitballs, and standardizing clean baseballs

Ushered in power hitting and the rise of stars like Babe Ruth

🧠 The Takeaway:

Every one of these changes was likely met with resistance—with fans and players saying, “It won’t be baseball anymore if we change that.”

But these revisions didn’t kill the game. They built it.

Baseball didn't survive in spite of these changes—

It survived because of them.

Modern Baseball Governance Chronology

II. Pre-Standardization: The Roots in Rounders and Town Ball

Before baseball, there was a loosely defined family of bat-and-ball games, including rounders (popular in England) and town ball (played in early American colonies). These games had:

No formalized diamond structure

No set number of innings

Varying rules for outs (sometimes runners were hit with the ball to record outs—known as “soaking”)

Minimal organization or enforcement

By the early 19th century, variations of town ball were spreading through northeastern cities like New York, Boston, and Philadelphia—but no uniform version of the game existed.

III. The Knickerbocker Rules (1845): The Beginning of Order

The first formal rulebook was drafted in 1845 by Alexander Cartwright and the Knickerbocker Base Ball Club of New York. This marked the game’s first major codification and revision.

Key rules introduced:

The diamond-shaped infield

Three outs per inning

Tag-outs (ending the practice of “soaking”)

"Soaking" (also known as "plugging" or "patching") was a method of putting a runner out in early bat-and-ball games—particularly town ball and rounders, the immediate precursors to modern baseball.

What it involved:

In soaking, fielders could get a runner out by throwing the ball directly at them while they were running the bases. If the thrown ball hit the runner—typically below the neck—they were ruled out.

Historical context:

Soaking was common before the mid-19th century, especially in informal or schoolyard versions of baseball.

It reflected the more chaotic, unsanitized nature of early bat-and-ball play.

Because early baseballs were softer and less standardized, soaking was generally not dangerous (though still unpleasant).

The practice began to fade as the game became more formalized, competitive, and safety-conscious.

Decline and abolition:

The Knickerbocker Rules of 1845, often considered baseball’s first formal rulebook, banned soaking in favor of tagging the runner or catching fly balls.

This shift was critical to differentiating baseball from rounders or town ball, making it less violent and more skill-oriented.

Abolishing soaking was a turning point in transforming bat-and-ball games into a modern sport with complex defensive and strategic dynamics.

Why it mattered:

Eliminating soaking:

Reduced physical risk

Required greater accuracy and strategy from fielders

Created more dramatic and tactical baserunning

Helped legitimize the game for adult competition and eventual professionalization

In short, the death of soaking helped baseball evolve from chaotic folk game to refined spectator sport.

Foul territory

The concept of the strike zone

While still amateur and largely social, these rules laid the groundwork for modern baseball. However, early baseball was far from standardized—rules varied by region, and games were primarily recreational.

IV. The National Association and the Rise of Competition (1857–1871)

In 1857, the National Association of Base Ball Players (NABBP) was formed to unify the rules across clubs.

Major revisions included:

Introduction of a 9-inning game

Standardized team sizes (9 players per side)

Regulation pitching distance (initially 45 feet)

A ban on catching a ball on the first bounce for an out (introduced in 1864)

Importantly, professionalism began to emerge as talented players were secretly paid. In 1869, the Cincinnati Red Stockings became the first openly professional team.

This prompted a division between amateur and professional baseball, setting the stage for organized leagues.

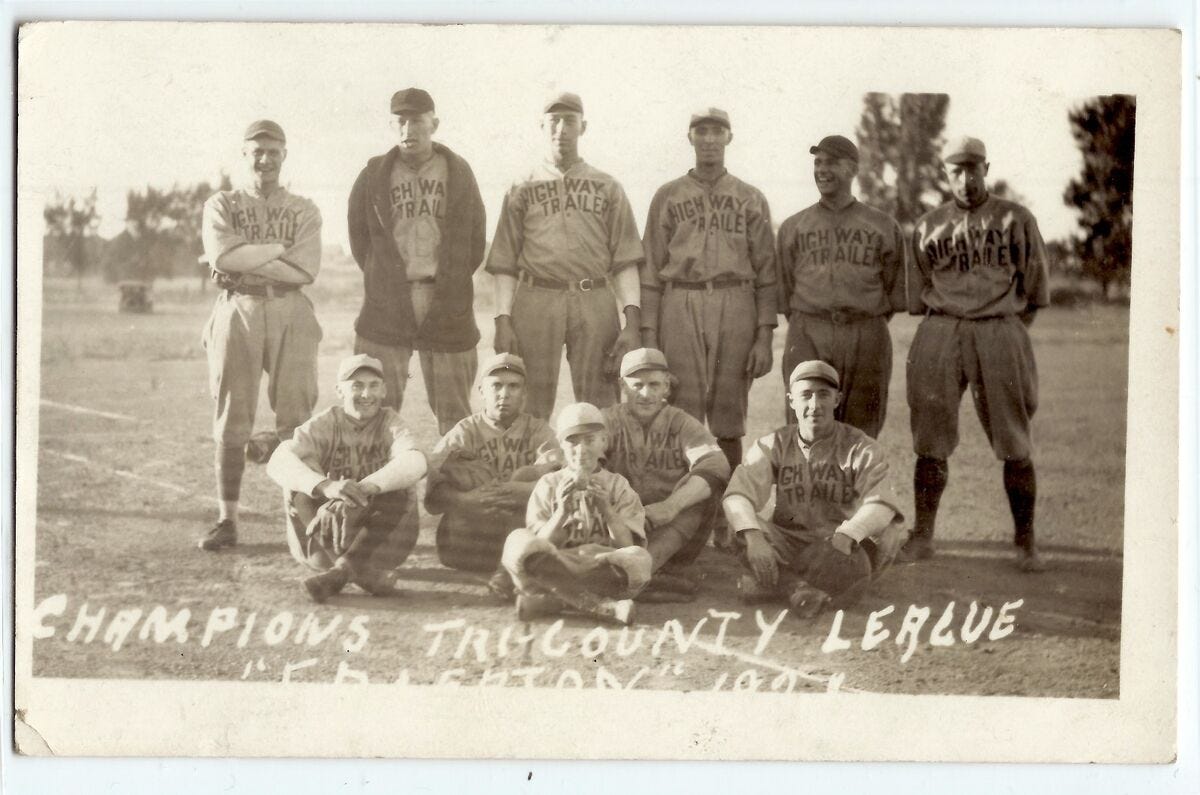

V. The National Association of Professional Base Ball Players (1871–1875)

The first professional league was formed in 1871, but it was short-lived and riddled with:

Gambling scandals

Inconsistent scheduling

No centralized enforcement authority

Still, the era prompted several pivotal rule changes:

Pitching restrictions were loosened

Walks were instituted (initially after 9 balls, later reduced to 4)

The “fair/foul hit” distinction was refined to penalize strategic exploitation

These years proved that baseball needed stronger governance and a more audience-friendly format.

VI. The Formation of the National League (1876): Discipline and Structure

Founded by William Hulbert, the National League (NL) introduced the first successful professional league model.

Innovations included:

Franchise exclusivity (teams had set territories)

Schedules enforced by league office

Umpires employed by the league

Player contracts and reserve clauses

This gave baseball legitimacy and order—but gameplay remained raw. Pitchers still threw underhand (until 1884), and glove use was still evolving.

VII. The Pitching Revolution (1880s): Strategy Takes Shape

Pitching underwent its most radical evolution during this decade.

Key rule revisions:

1884: Overhand pitching legalized

1887: Four strikes removed; the four-ball walk finalized

1893: Pitching distance extended to 60 feet, 6 inches (from 50 feet)

These changes shifted baseball from a hitter’s game to a balanced contest between pitcher and batter. The mound distance in particular transformed pitching into a craft requiring skill, strategy, and stamina.

VIII. Defensive Innovation and Equipment Standardization

As pitching improved, so too did defensive play:

Catchers began to wear chest protectors and masks (1870s–80s)

Gloves evolved from thin leather mitts to more padded forms

Field dimensions became more standardized

Fielding improved dramatically, reducing scoring from the high-offense days of the 1870s. Errors dropped, and defensive metrics began to emerge.

IX. Cultural and Institutional Shifts (1890s–1910s)

During this period, baseball began to embed itself into the national identity:

The American League (AL) formed in 1901 and merged with the NL in 1903, inaugurating the World Series

Stadiums were built with fixed seating (e.g., Forbes Field, Fenway Park)

Night games, commercial broadcasting, and African-American leagues emerged later

Additionally, foul balls began counting as strikes (1901 NL, 1903 AL), and the infield fly rule was instituted to prevent deception.

X. Conclusion: Revisions as the Path to Greatness

Baseball did not become the American pastime by resisting change. It earned that status precisely because it adapted. Rule revisions eliminated ambiguity, balanced offense and defense, and made the game fairer and more competitive. From the chaos of town ball to the strategy of pitching duels, every major transformation improved the game’s legitimacy, safety, and audience appeal.

The lesson is clear: tradition may inspire nostalgia, but it is revision—not reverence—that builds great games.