Grievances

The quiet triumph of grievance culture is not in storming institutions, but in slowly suffocating them with grievances disguised as justice. It does not conquer through force, but through accusation — through a thousand tiny moral victories won by those who wield victimhood like a sword and shame like a leash. And behind every grievance is not a movement, but a person — often someone frightened, confused, or petty — driven not by principle but by a desire to dominate under the guise of being dominated.

But for every grievance aired, someone else must be cast as the villain. And so the ideology feeds: it invents oppressors where none exist, fabricates harm where none was done, and leaves in its wake the real, unseen victims — people smeared, canceled, isolated, ostracized, marginalized or destroyed not for what they did, but for what they represented. The man who spoke too plainly. The woman who refused to kneel. The child who asked the wrong question.

And yet, it is not the ideologues alone who are to blame. The greater betrayal belongs to the cowards and the spineless — those who saw the madness and said nothing, who bent the knee to keep their peace, who chose the convenience of capitulation over the inconvenience of conviction, who passed down lies because they feared the truth might cost them comfort. A civilization does not collapse when enemies storm its gates. It collapses when the people inside no longer believe it is worth defending.

The genius of modern grievance culture lies not in open revolution, but in its parasitic patience. It advances not by argument, but by grievance — feeding off the pity it demands, and the guilt it manufactures. Each concession to its cause seems trivial, even noble: a policy here, a pronoun there, a curriculum shift, a statue removed. But over time, the ground gives way beneath our feet, and we awaken in a world where the weak rule by accusation, strength is pathologized, and victimhood has become a throne from which the mediocre reign.

In rewarding resentment, we have institutionalized failure — and called it justice.

Where it started

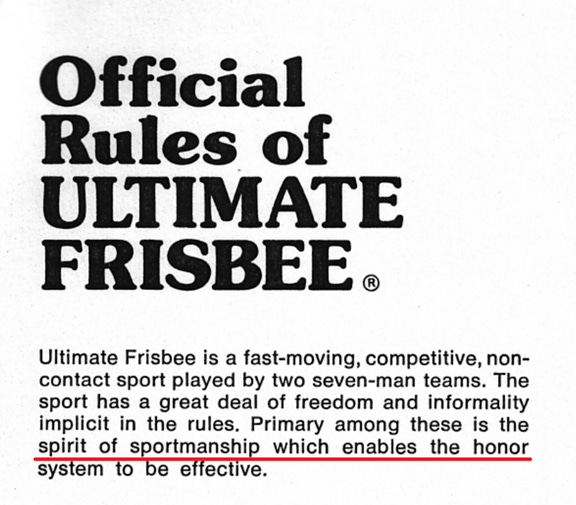

To give you an idea of the corrosive nature of Grievance Culture, Ultimate Frisbee’s Spirit of the game went from this in 1976:

Where it’s going

To this in 2025 (each one of these line items was either the result of either some grievance or the roadmap for filing grievances (or both)):

If you look at each of the items in the below excerpt from the 2024-2025 USAU Official Rules through the lens of Grievance Studies, you can make a case for how each one of these highlights the inverse of a grievance. For example,

A. Spirit of the Game is a set of principles which places the responsibility for fair play on the player.

could be read as a entitlement for anyone to file a grievance against anyone who is perceived to be not playing fair and to label them accordingly (even though the rules are inherently unfair) and therefore an unresponsible player.

From this perspective, you can see that almost the entirety of the section below is a guideline for defining what is and what is not a grievance.

Because the Grievance culture is based on the oppressor/oppressed dichotomy, then the Spirit of The Game soliloquy below also helps create definitions for how to separate the oppressed from the oppressors.

This might seem like a stretch, but trust me. Once you see it, you can’t unsee it.

Case in point:

2.D.9. be conscious of the impact of your words and body language;

Enjoy!!

Preface

Ultimate is a sport that inspires players and fans alike because of its ability to develop and showcase the athleticism, skill, teamwork, and character of its participants. The arc of the disc in flight, the opportunity for each individual to contribute equally to their team’s success, and the trust given to each player to know and uphold the rules make ultimate a sport that is embraced for its fun and excitement on the field and for the community beyond it. As a low-cost sport requiring minimal equipment, offering single and mixed-gender play, and providing a format that builds communication and conflict resolution skills, ultimate provides a welcoming, high value experience for players and fans from a diverse set of backgrounds and experiences. The Official Rules of Ultimate 2024-2025 describes how the game is played, including how players self-officiate and apply the principles of Spirit of the Game in competition.

1. Introduction

1.A. Description: Ultimate is a non-contact, self-officiated disc sport played by two teams of seven players. The object of the game is to score goals. A goal is scored when a player catches any legal pass in the end zone that player is attacking. A player may not run while holding the disc. The disc is advanced by passing it to other players. The disc may be passed in any direction. Any time a pass is incomplete, a turnover occurs, resulting in an immediate change of the team in possession of the disc. Players are empowered to self-officiate using a framework governed by the principles of Spirit of the Game.

1.B. Rules Variations

1.B.1. Appendices included in these rules outline rules changes and additions specific to several variations of the sport.

1.B.2. Event Organizer Clause: The event organizer may modify rules relating to game logistics in order to suit the event. Examples include game length (game total), time limits (time caps), halftime length, number of timeouts, starting time point assessments, uniform requirements, and observer operations. Any such change must be established before competition starts.

1.B.3. Captain’s Clause: For games not subject to the event organizer clause, a game may be played under any variation of the rules agreed upon by the captains of the teams involved. Otherwise, any rules variations are subject to approval by the event organizer.

1.C. General vs. Specific Rules: Many of these rules are general in nature and cover most situations. However, some rules cover specific situations and override the general case.

2. Spirit of the Game

2.A. Spirit of the Game is a set of principles which places the responsibility for fair play on the player. Highly competitive play is encouraged, but never at the expense of mutual respect among competitors, adherence to the agreed upon rules, or the basic joy of play.

2.B. All players are responsible for knowing, administering, and adhering to the rules. The integrity of ultimate depends on each player’s responsibility to uphold the Spirit of the Game, and this responsibility should remain paramount.

2.C. It is assumed that no player will intentionally violate the rules; thus there are no harsh penalties for inadvertent infractions, but rather a method for resuming play in a manner that simulates what most likely would have occurred absent the infraction. An intentional infraction is cheating and considered a gross offense against the Spirit of the Game. Players are morally bound to abide by the rules and not gain advantage by knowingly committing an infraction, or calling one where none exists.

2.C.1. If a player intentionally or flagrantly violates the rules, the captains of each team should discuss the incident and determine an appropriate outcome, and are not bound by any outcome dictated by these rules.

2.C.2. For behavior warranting sanctions pursuant to Appendix B The Misconduct System, team captains or coaches may remove players on their team from the game for one point or any longer duration, to help promote SOTG. Removal shall occur after a point has been scored and before the next pull. However, in cases of ejection-worthy behavior, removal can occur at the next stoppage of play during the current point, with permission of the opposing captain. Spirit captains should be consulted prior to removal of a player. A captain or coach may permit a removed player to return to play at any time, consistent with rules on substitutions. If a player is substituted by a team in accordance with this rule, the other team may substitute a player.

2.D. Players should be mindful of the fact that they are acting as officials in any arbitration between teams. Players must:

2.D.1. know and abide by the rules;

2.D.2. make calls only where an infraction is significant enough to make a difference to the outcome of the action or where a player’s safety is at risk;

2.D.3. be fair-minded and objective;

2.D.4. be truthful;

2.D.5. explain their viewpoint clearly and concisely;

2.D.6. allow opponents a chance to speak;

2.D.7. listen to and consider opponent’s viewpoint;

2.D.8. treat your opponents with consideration;

2.D.9. be conscious of the impact of your words and body language;

2.D.10. resolve disputes efficiently;

2.D.11. make calls in a consistent manner throughout the game and from player to player; and

2.D.12. acknowledge potential bias and preconceptions in order to treat every player equitably

[[Players are required to “explain their viewpoint clearly and concisely” and “resolve disputes as quickly as possible.” As such, most discussions should not exceed thirty seconds before either reaching a resolution or requesting an observer to resolve the dispute. If both players have had an opportunity to state their viewpoint and it is clear that an agreement will not be reached, players have an obligation to accept that the call is contested and resolve it as such. Where a dispute exists regarding what a rule says, the players may agree to consult a rulebook.]]

2.E. The following are examples of actions to support good spirit. While the absence of these actions is not necessarily an indication of poor spirit, the examples illustrate three core tenets of Spirit of the Game — mutual respect, adherence to the rules, and the basic joy of play:

2.E.1. playing safely by actively avoiding unnecessary body contact;

2.E.2. working as a team to ensure that all players have an excellent knowledge of the rules;

2.E.3. bringing up spirit issues with opponents as early as possible;

2.E.4. establishing lines of communication to address spirit and safety issues (e.g. spirit captain pregame and halftime meetings; calling a spirit timeout if needed);

2.E.5. informing a teammate if they have made a wrong or unnecessary call, caused a foul or violation, or need a clarification of a rule;

2.E.6. retracting a call when you no longer believe the call was necessary or believe that it was made in error and should not have been called;

2.E.7. celebrating exciting plays and good spirit by both teams;

2.E.8. touching base with an opponent on the sideline after a contentious interaction;

2.E.9. discussing and/or making calls about contact that could be considered a foul in order to keep players safe;

2.E.10. connecting with or introducing yourself to an opponent on the sideline;

2.E.11. keeping communication open and engaging in a way that seeks to de-escalate disputed situations; and

2.E.12. participating in a pre- or post-game spirit circle that includes spirit highlights and constructive spirit feedback (if needed) for each team;

2.F. The following actions are clear violations of the Spirit of the Game and must be avoided by all participants:

2.F.1. reckless play or dangerously aggressive behavior;

2.F.2. intentional fouling or other intentional rule violations;

2.F.3. taunting or intimidating opposing players;

2.F.4. celebration that is targeted towards an opponent in a negative or aggressive manner;

2.F.5. intentionally damaging equipment;

2.F.6. making calls in retaliation to an opponent’s calls or other actions;

2.F.7. allowing preconceived expectations, biases (e.g., microaggressions), or previous interactions or encounters with a player or team to affect how game situations are reacted to and judged;

2.F.8. calling for a pass from an opponent; and

2.F.9. other win-at-all-costs behavior.

2.G. Teams are guardians of the Spirit of the Game, and must:

2.G.1. take responsibility for teaching their players the rules and good spirit;

2.G.2. discipline team members who display poor spirit;

2.G.3. provide constructive feedback to other teams about what they are doing well and/or how to improve their adherence to the Spirit of the Game; and

2.G.4. be aware regarding the potential for implicit biases to impact play and Spirit of the Game.

2.G.4.a. Players and team leaders should acknowledge and recognize that the implementation of Spirit of the Game (SOTG) is susceptible to bias. Team leaders should be mindful of and encourage their teammates to be mindful of their own biases when considering and discussing interactions with, and impressions of, other teams as well as their own team. Understand that intent and impact are not the same. The intent of a person’s statement or gesture may be neutral or positive to them, but the impact of what they say or do may be harmful or hurtful to others.

2.H. In the case where a novice player commits an infraction out of ignorance of the rules, experienced players are obliged to explain the infraction and clarify what should happen.

2.H.1. Coaches should teach players to come to a resolution on their own. Coaches may not make calls from the sideline nor offer their opinion on a play. If asked during a dispute coaches may offer rules clarifications. After a dispute, and when the player is not playing, a coach may talk to their own player about the dispute and offer opinions and guidance.

2.I. Rules should be interpreted by the players directly involved in the play, or by players who had the best perspective on the play (3.A). Players may seek the perspective of sideline players to clarify the rules, and to assist in making the appropriate call (3.A.1, 3.A.1.a). Sideline players should not interject unless their input is requested. [[It is acceptable for sideline players to state that they have input, but they should avoid interjecting unless requested.]]

2.J. Players are responsible for making all calls except where specific rules designate non-players to make calls. [[For example, offsides on the pull or when observers keep time.]]

2.K. If after discussion players cannot agree, or it is unclear:

2.K.1. what occurred in a play, or

2.K.2. what would most likely have occurred in a play,

the disc is returned to the thrower.